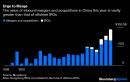

(Bloomberg Opinion) — To look at the politics of it, you might think that four years of President Donald Trump’s trade war on China were just starting to bear fruit as he prepares to leave office.Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga used his first foreign tour since taking office to visit Vietnam and Indonesia, notably China-skeptical allies, and push for a strengthening of bilateral supply chains that would avoid the region’s 800-pound gorilla. Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen, who has been pursuing a similar policy, used a major investment by Microsoft Corp. last month to encourage allies to “re-imagine supply chains”: Australian exporters should actively explore destinations other than China, Trade Minister Simon Birmingham told Australian Broadcasting Corp. radio Monday, after Beijing was reported to have ordered a halt last week on imports of a swathe of Australian products including lobster, wine and coal.Washington’s recent line on China looks likely to carry over into the next administration, too. President-elect Joe Biden will make China “play by the international rules,” he promised in the final presidential debate last month, arguing his position would, if anything, be tougher than Trump’s. Despite all the apparent movement, the facts on the ground look rather different. Far from succeeding in isolating China over the past four years — and in spite of the autarkic fears raised by President Xi Jinping’s promotion of self-reliance — the Trump era has seen the country integrated ever more deeply into the global economy. As we’ve argued, the forces placing China in the middle of the world’s trade and investment flows are stronger than a pandemic or any one U.S. president.Take trade. China’s exports grew at a faster-than-expected 11.4% in dollar terms in October, the country’s customs authorities reported over the weekend. Exports through the past four months alone have been roughly in line with their level during the whole of 2006, at a time when talk of China as the “world’s factory” hit an apex.Imports have been improving to a lesser extent, too, after nearly two years of decline. Still, far from narrowing the trade surplus — as the Covid-free domestic economy has recovered faster than those of other countries — the past year has actually widened the gap. In dollar terms, four of the strongest months on record for China’s trade surplus have occurred since May.For all that the likes of Suga and Trump have been promoting economic disengagement from China — and for all that China’s own more authoritarian turn has made the country a more challenging prospect for foreign investors — that love affair applies to investments as well as trade flows.After plummeting in the early months of the Covid pandemic, foreign direct investment into China has been accelerating since April, with the sum of foreign capital utilized in September up 25% from a year earlier.One visible example of that trend has been the well-publicized rush of Chinese companies into U.S. initial public offerings in recent months. It’s not the only instance, though. Indeed, 2020 looks on track to be the strongest year in history for inbound takeovers of mainland businesses, with 2019 and 2018 taking second and third place:Remarkably, this inbound flood of foreign capital isn’t even the most dramatic part of the investment picture. As China’s trade and current account surpluses have risen, the financial and capital account has balanced with a sharp move in the opposite direction. The deficit on those accounts in the third quarter — the extent to which Chinese purchases of foreign net assets exceeded reverse flows — came to $94.2 billion, the widest such figure since 2008, according to preliminary data reported last week. Even if part of that number gets reclassified as “errors and omissions” in the final reckoning, the mix of official capital outflows and ones disguised as “errors” will still be among the largest on record:This shouldn’t be too much of a surprise. Years of accumulated investments in China’s trade capacity aren’t going to stop their buying-and-selling activity across borders just because of some tough political rhetoric. At most, any vaunted pivot in the world’s supply chains will only see China take a declining share of a rising volume of cross-border flows, and such a shift may take years. An absolute decline in Chinese trade with the world remains an extremely unlikely prospect. That’s probably a good thing, given the way commercial ties buff away the sharp edges of international relations and reduce the chance of conflict.In the meantime, China has one of the world’s biggest domestic markets, an array of tax and land incentives for inbound investors, and a labor force that is still denied the ability to push for better conditions. For global capital, this mix is as attractive as it was before Donald Trump had ever uttered the word “China.”This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinionSubscribe now to stay ahead with the most trusted business news source.©2020 Bloomberg L.P.,

,